Wrist pain may vary, but if you see an unusual deformity on your wrist, it could be a sign of Smith’s fracture.

In anatomy, the radius bone links the hand to the elbow. It’s one of the outer bones that make up the forearm – the other being the ulna – when viewed with the palm facing forward.

In a normal hand, gently make wrist circles or forearm rotations. That’s the radial bone doing its job. And the part of it connected to the wrist joint is called the distal radius. It’s the end closest to the hand that is especially susceptible to radial fracture.

A radial fracture is a specific kind of broken wrist. But how will you know if your ‘deformed wrist’ relates to this? To give you an idea, this guide will walk you through what Smith’s fracture is.

Smith’s Fracture Explained

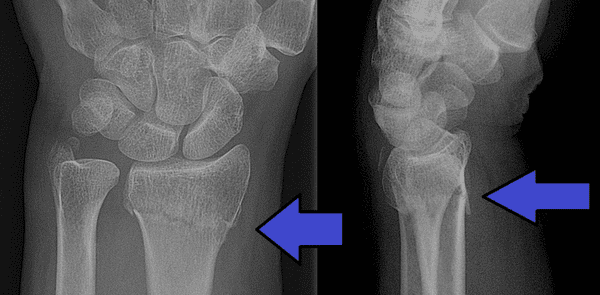

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Smith’s fracture is a break involving the distal radius, causing volar angulation. Meaning a part of the wrist is either at a loss of axial alignment or tilted. This explains the degree of angulation or displacement of the bone’s normal axis when viewed in an X-ray.

The distal radius fracture is similar to the common fracture called Colles. Except that it occurs from trauma, such as from falling on an outstretched hand or a flexed wrist.

There are three types of Smith’s fracture, categorised as type I, type II, and type III.

- Type I. A common fracture with a transverse break outside the wrist joint.

- Type II. Also known as Barton fracture – an intra-articular fracture. It occurs on the articular surface of the radial-ulnar joint, such as the joint surface.

- Type III. The least common type that involves a juxta-articular oblique fracture. It occurs as a curved or angled break at the wrist joint’s articular surface.

Regardless, it can happen to anyone.

Colles vs Smith’s Fracture

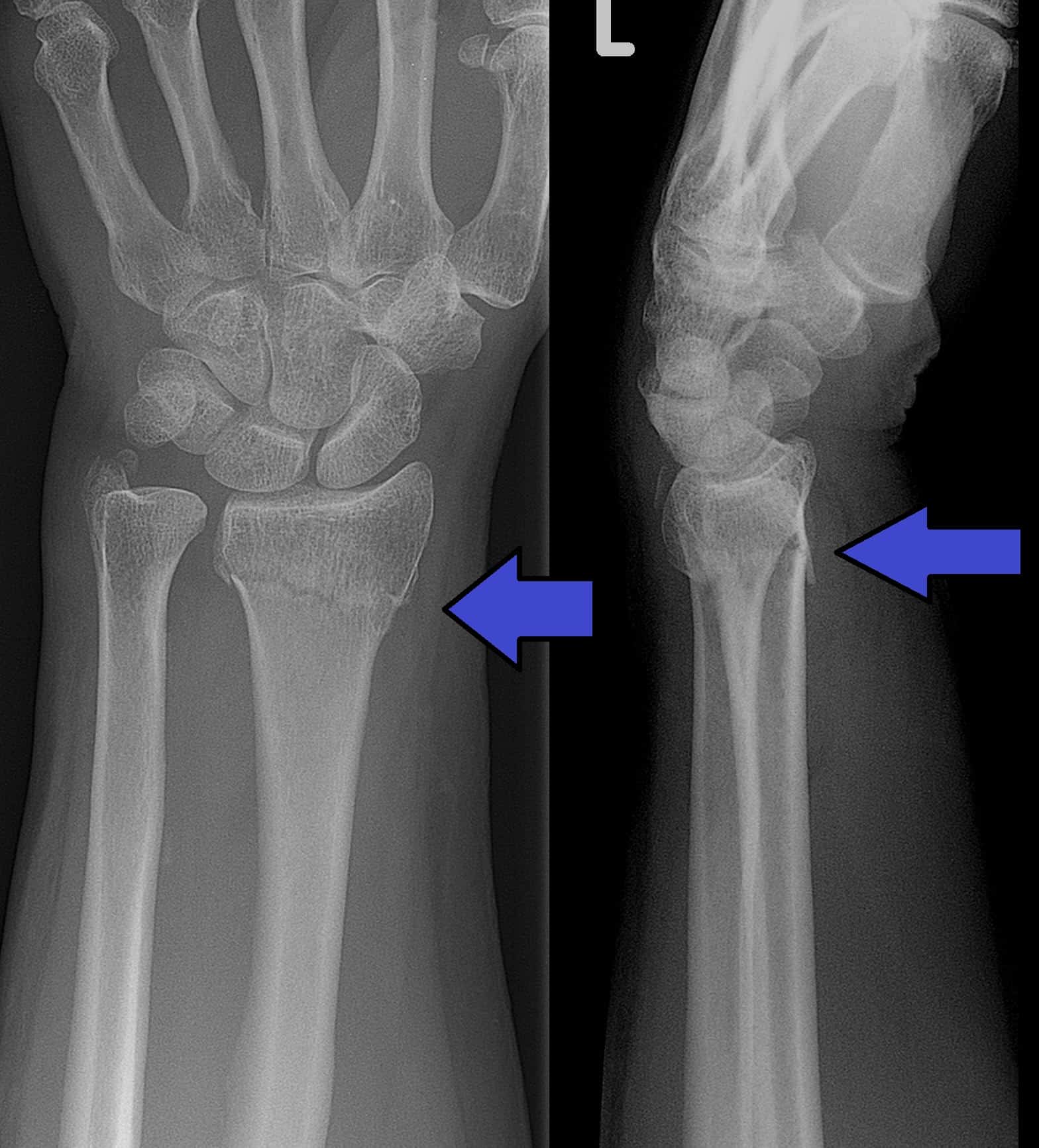

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The displacement of fractures is what differentiates the two. A Smith’s fracture, as explained, concerns a volar displacement.

A Colles fracture, in contrast, results in dorsal displacement. It causes the bone fragment to bend towards the back of the hand. Colles fractures are the most common type of distal radius fragment.

In simple terms, Smith’s has the distal radius pointing forward and backwards with Colles.

The Fernandes Classification

A distal radius fracture can be classed based on the mechanism of injury that caused the break. There are five distinct fracture patterns described by D.L. Fernandez, MD. These are all based on the direction and degree of force applied to the radius in the fall:

- Bending. Either Smith’s or Colles, such a fracture can be caused by a bending where the hand is extended backwards – vice versa.

- Shear. As the fracture occurs, the bone shears where one end moves in one direction, the other in the opposite way.

- Compression. The hand and wrist bones can be compressed against the flat surface of the distal radius. This happens in falls from a height, affecting the carpal bones (smaller wrists).

- Fracture-dislocation. The carpal bones are dislocated from the distal radius. A high-energy type of fracture, e.g. falling from a height higher than standing height.

- Complex. A combination of unfortunate injuries. Extensive damage to the joint surface, distal radius fragmentation, and shaft damage. Requires a mixture of treatments to reconstruct the damaged elements.

Note: Low-energy fractures result from falling from standing height or less.

Signs and symptoms

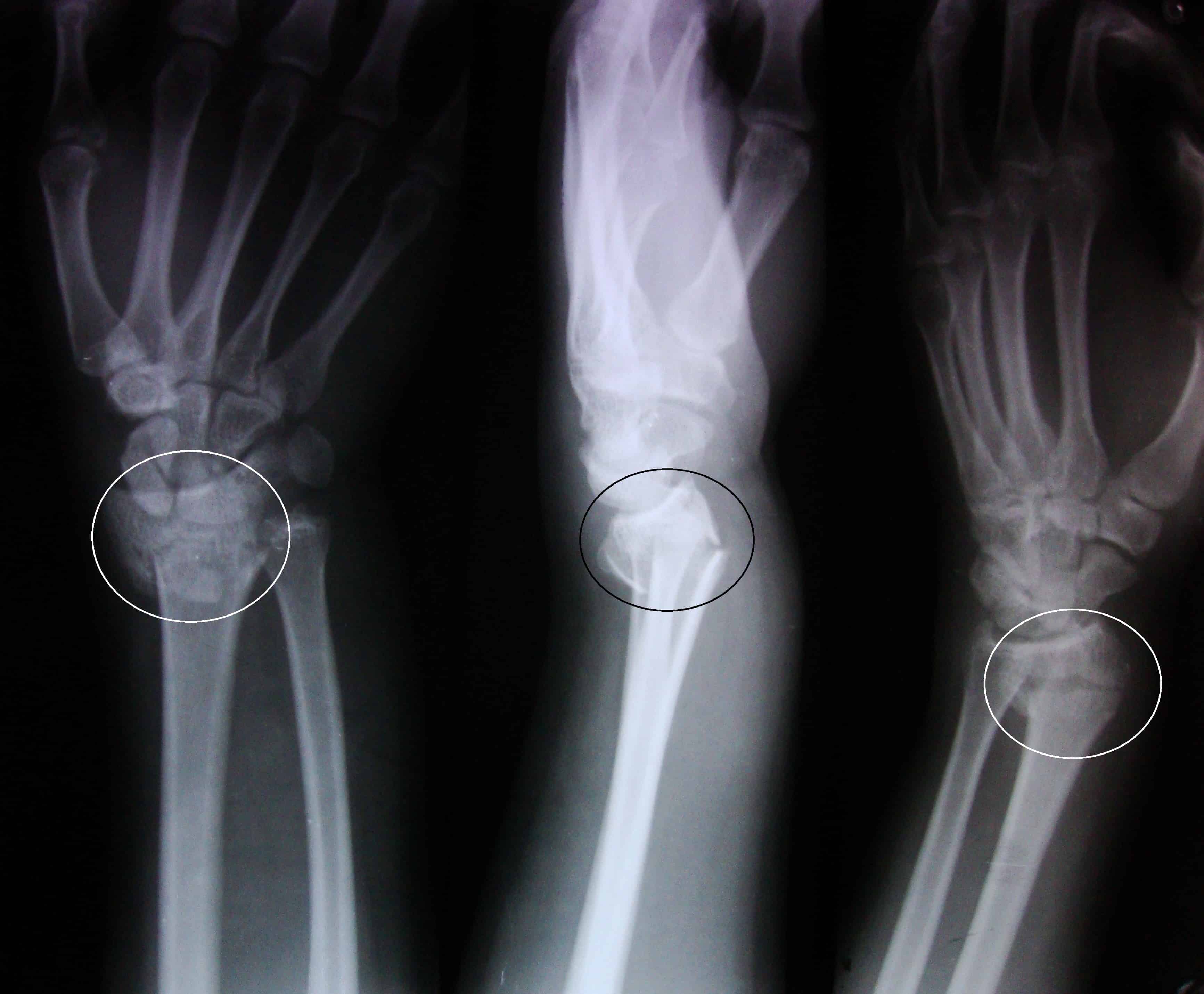

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Smith’s fractures often appear as a deformity on the distal forearm. However, the displacement of fracture may be difficult to assess without imaging tests.

Generally, it may present with swelling, pain, and decreased range of motion in the wrist. If the neurovascular status is affected, tingling and numbness may also be experienced. Other symptoms include:

- Bruising or discolouration

- Unusual deformity on the wrist that’s not usually there

- Tenderness in the area of the fracture

- “Pins and needles”

If you suspect a Smith’s fracture, you should try not to move the distressed wrist. Get it examined by an Orthopaedic as soon as possible to treat the distal radius fragment.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a thorough medical examination, followed by a physical exam. Evaluation is then followed by an imaging test, such as an X-ray, to distinguish the type of fracture.

Additional radiographs may also be used to assess injuries in soft tissues. This may include traction or a CT scan. Even an MRI for confirming or ruling out damage to other parts of the wrist, like muscles, tendons and ligaments.

Overall, the needed test will depend on the cause and severity of the injury.

Causes

There are two possible ways to develop a Smith’s fracture. First, falling onto your wrist while it’s flexed. Second, a direct blow to the back of the wrist.

Osteoporosis, a weakness in the bone, can also increase the risk of distal radius fracture. But this doesn’t mean it can’t occur in healthy bones. High-force incidents like a fall of a bike or car crash can also be contributing factors.

Treatment

Treatment may vary on severity, age, and activity level. There are both nonsurgical and surgical treatment options. Usually, the doctor will recommend non-surgical treatment, such as:

- Immobilisation. Wrist support may be required. Splinting can last for three to five weeks, whereas a cast can take longer – six to eight weeks, tops.

- Closed reduction. Severe breaks may need a closed reduction to set or realign the bones. It’s a non-surgical procedure where the Orthopedic surgeon pushes and pulls the arm and wrist. This will help line up the distal fragment. A cast or splint in the wrist will be provided, and a follow-up checkup is necessary. Note: You may request a local anaesthetic to numb your wrist and arm or make you sleep during the procedure. For one, it may hurt.

- Surgery. If the fracture is more significant, a surgical correction may be advised. The surgeon will use one of the options to hold the bone in the correct position, which will be discussed with you. Options include a cast, metal pins, plates, and screws.

Physical therapy may be suggested a few weeks after surgery to improve symptoms. For minor injuries, ice packs and elevation usually help. Pain medication (NSAIDs) may also be prescribed to control pain during recovery.

Please note that this post only intends to simplify what Smith’s fracture is. Do not rely on it completely, particularly for self-diagnosis. Always get your condition checked by a trusted doctor for clinical guidelines.