As the discussion over whether the Premier League should follow in the in the footsteps of its European neighbours and implement a winter break, PhysioRoom takes a look at the statistics behind the debate

There’s certain traditions you’ll find this time of year. As soon as the clock strikes twelve on December the 1st, Christmas songs batter our eardrums in to a wintery submission. Out comes the discount shop tinsel, crudely sellotaped around your place of work in an effort to forcibly cheer. Someone has probably made a fool of themselves at the office work ‘do’ after having one too many, and now must face the indignation being referred to as the guy who “accidentally headbutted Joanne while drunk at the Christmas party” for the next year. But there’s no finer tradition than that of the frustrated European manager working themselves in to a stupor and expressing absolute bafflement at the Premier League’s lack of a winter break.

As we’re well aware, Europeans attempting to enforce their ways on the British people has never backfired in any way, ever. So, long have there been calls for English football to cast aside their festive programme and embrace a rest in December or January.

The perceived benefits being a boost in summer performance for the national team. Who knows whether an extra X% of fitness would have helped England overcome the mighty Iceland in the summer, but former UEFA President Michel Platini, whose opinion is seemingly far cheaper to acquire than his vote, once said English players were like ‘lions in the winter and lambs in the summer’.

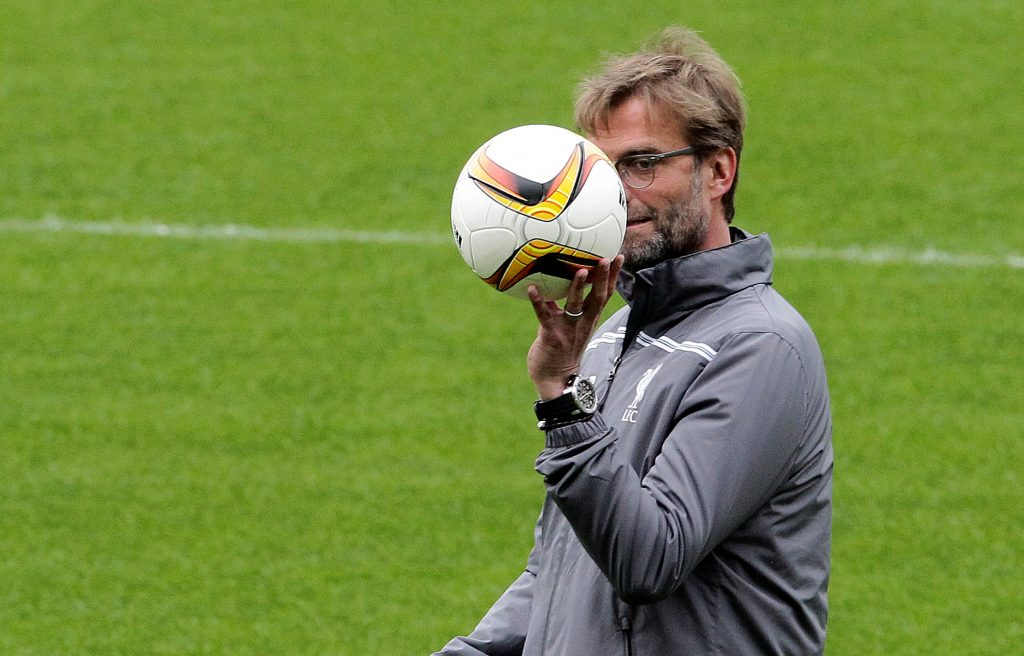

And it’s not just disgraced ex-bureaucrats who think along these lines. People we quite like, such as Jurgen Klopp, also feel that way. Back in October the German, looking ahead to his side’s festive period and their game versus Sunderland just 48 hours after playing Manchester City, said:

“I don’t know why we play Monday. Is January 2 a special day in England?

“Forty-eight hours between two games – how does this work? And then you will sit there and say: ‘You didn’t perform too well, how did this happen?’ or ‘Injuries. Oh?’

“How do you prepare a team for this? Do you say: ‘Only 50% against City because we have Sunderland on Monday?’.

“It doesn’t sound like it is right. Everyone is asking: ‘Why England is not too successful in big tournaments?’

While Klopp, and other supporters of the winter break continue to call for it in order to help prevent injury and burnout, some, like Arsene Wenger value tradition, last year saying:

“I would cry if you changed that because it’s part of English tradition and English football.

“It’s a very important part of us being popular in the world, that nobody works at Christmas and everybody watches the Premier League.”

In contrast, former England manager Sam Allardyce, who has recently enjoyed his own extended winter break, said last year:

“There’s a lot of research that shows European teams have less injuries after their mid-season break than we do.

“We continue to have a lot of injuries. I’ve watched teams play. Last year I think three Chelsea players got injured [at Christmas time] in one game because of the fatigue. Especially those boys in the Champions League, they go through a lot.”

So it seems everyone has an opinion, but what do the numbers say? Does the lack of a break cause a higher rate of injuries around the festive period? Well strap yourself in, you’re about to find out.

We looked at the last four years, 2012 to 2015 and the number of players struck down by a winter ailment.

In two of the four years in question, December was the most prolific month for injuries.

- In 2012 we see November being the highest month for injuries with 155, which for context is 28% above the yearly average of 109. December was third in the table with 133 injuries, which is two fewer than that of September.

- In 2013 we found that December was indeed the month that saw the most injuries occur with 146, again 28% above that year’s average of 105.

- 2014 again saw December being the most affected month with 145 injuries, 24% above the yearly average of 111. This was closely followed by November and January of that year.

- Finally, 2015 saw January as its biggest offender for knocks with 149, a whopping 31% above the yearly average of 103. Second in 2015 was February with 120.

But what can we gather from these statistics?

It’s more than safe to say that the months of November, December and January experience spikes in injury activity compared to the rest of the year. However, this may be attributed to natural wear and tear rather than a lack of a one or two-week break.

With that said, when looking at the stats in some finer detail, you discover that the season of 2014-2015 experienced a prolonged period of higher injuries from November to January. And even February of 2015 was the second highest month for injuries of that calendar year. It’s worth remembering this season was off the back of the World Cup in Brazil, which may have been a contributing factor.

In fact whichever way you look at it, be it by calendar year or by an August-May season perspective, the months of November, December and January are above the average number of injuries, except in 2015 where November fell just below. December of 2015 was also lower than that of any other year, again perhaps leading us to the conclusion that international football, or the lack thereof, can be a factor.

So perhaps, given these figures, some sort of non-linear thinking may need to added to the discourse. Rather than the debate boiling definitively down to winter break or no winter break, it may be a good idea to entertain the idea of biyearly breaks structured around the international football schedule. Or in other words, in the seasons after a World Cup or European Championship, give the players a short break in the name of injury prevention.

This would ultimately fly in the face of those demanding a break with the sole intention being to help the national team in the following summer, but players can’t feature in major championships if they’ve broken down due to over-exertion and find themselves suffering a long term injury.

Of course, having been pulled every which way by the ever-growing demands and variables of modern football, it’s vitally important for English football that some sort of tradition is maintained. But given a January break wouldn’t interfere in the slightest with our need for a festive feast of football, it would be foolhardy to not at least entertain the idea.

How this could be implemented is a question for the combined pool of fixture boffins at the FA and the Premier League. And given no parties in this situation are willing to budge over the scheduling of certain cup competitions like the FA Cup, the debate is sure to rumble on in winter time press-conferences around the country.

On this occasion, we may have to concede, as a country, and as a footballing culture, that we don’t do everything right, and that those pesky mainland Europeans may be leading the way.

Author: Chris Coates